Serious as a Heart Attack: The High Cost of ‘It’s Probably Nothing’

"Man, it feels like I pulled a fucking muscle,” I said, gingerly massaging the area between my left shoulder and chest. The sensation wasn’t so much ‘pain’ as it was discomfort. This was the evening of Wednesday, December 27th, a few hours after I’d finished helping a friend move a few pieces of furniture.

In the following days, my experience was a mix of normalcy, discomfort, and annoyance. There were extended periods when I felt completely fine, but these were intermittently interrupted by a return of the same discomfort to the same area. Notably, while the bouts of discomfort grew more frequent, they didn’t intensify. Given that I’d played sports in my younger years, I’m no stranger to the dull sensation of an overworked muscle—and considering that I had just been lugging furniture around, it seemed logical to attribute my discomfort to something akin to a muscle strain.

My concrete medical self-assessment began to crumble, however, on New Year’s Day when I awoke with the same feeling of discomfort, although dramatically more pronounced. After two hot showers and constant massaging of my shoulder, I popped a pile of Motrin and waited to see if that would do the trick.

Spoiler alert: it didn’t.

By 3 pm, I was sitting in my comfy chair reading about the differences between a muscle strain and the symptoms of a heart attack. Other than discomfort, I wasn’t experiencing any of the other listed tell-tale signs of someone having a heart attack, such as fatigue, heartburn, lightheadedness, nausea, shortness of breath, or cold sweats. At one point, while scouring medical websites for information, I shrugged off an alert from my Apple Watch Ultra 2 that warned my heart rate was high.

'Anxiety will do that,’ I told myself.

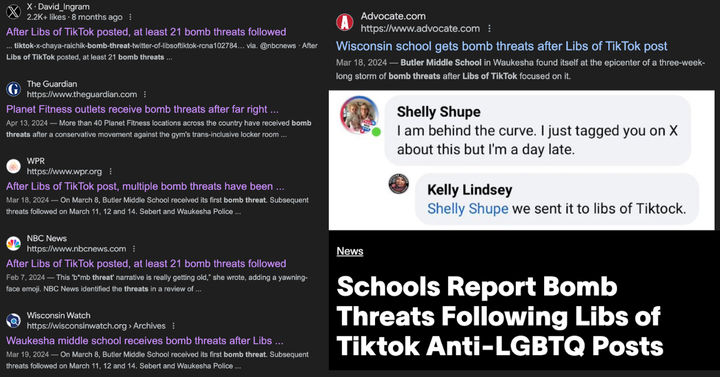

Denial, I would later learn, is a powerful and potentially deadly force. This is especially true when you've already self-diagnosed a muscle strain and when one is forced to reckon with a medical insurance system that deters people from seeking the medical care they need.

Right around 5:00 pm, long after the Motrin should have kicked in but clearly hadn’t, I surrendered to the possibility that my worsening symptoms might indicate a serious medical event was underway. "Fuck it, let’s go waste a pile of money at the hospital to find out I pulled a muscle,” I said.

I walked into Providence’s emergency department at around 5:30 pm and stood in line behind numerous individuals, including a woman whose son told me that she was COVID-19 positive and "not feeling well.” Although I was holding my left shoulder with my right hand at this point, I did what any good Blue Alaskan would do—I grabbed a mask from the wall and put it on.

The discomfort, now pressure, had me debating whether to jump the line and rush the plexiglass enclosure, but I wouldn’t have been able to live with myself if I later learned that I’d inconvenienced others over a 'strained muscle.’

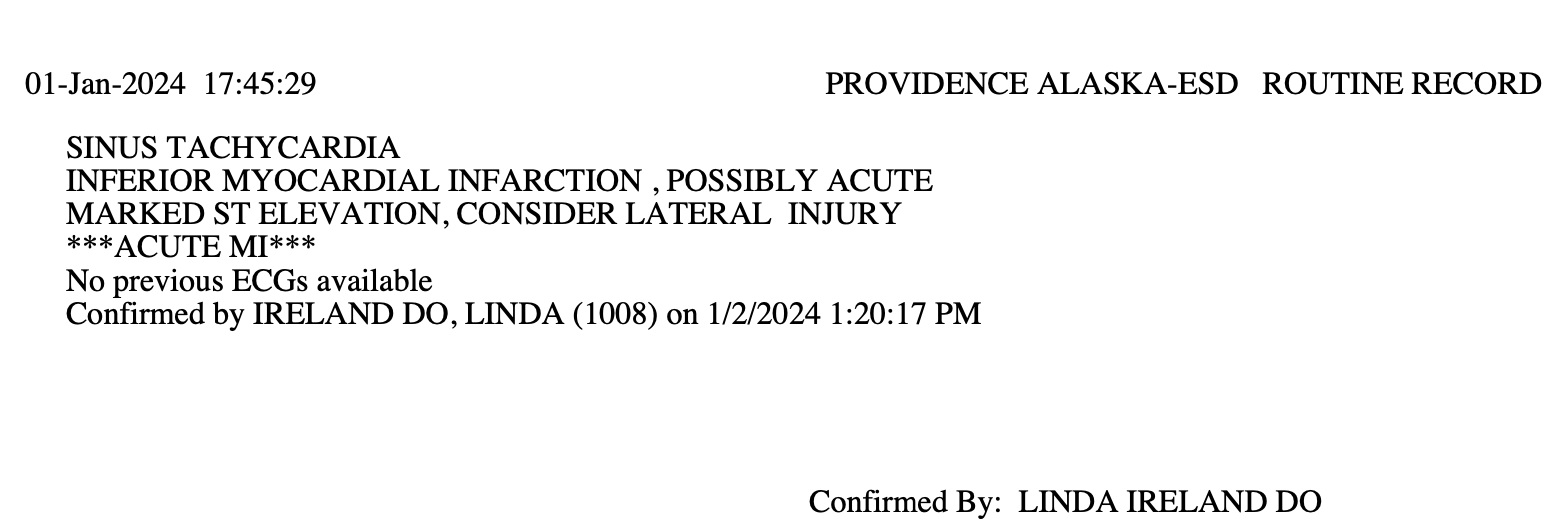

I arrived at the counter and stammered my symptoms, resulting in a nurse hitting a big button, whisking me through a door and rushing me around a corner while someone ordered me to lay down on a stretcher for a 12 Lead ECG test. A nice lady quickly and most efficiently placed the leads across my chest.

After staring at the screen for what seemed an eternity, she looked over her shoulder and shouted to someone I couldn’t see, "This guy needs a room, STAT.”

With haste, I was carted off to a nearby room where a woman approached, leaned in, and said, "Mr. Beck, things are about to get very busy. There will be a lot of people working on you, and it will feel overwhelming, but we’ve got you.”

It was after hearing those kind, reassuring words amid the rapidly unfolding insanity that I realized I may have very well waited too long to seek medical attention. As I sat on the stretcher answering questions while what must have been a dozen technicians, nurses, and doctors swarmed the room, I found a sense of gratitude for each passing second I didn’t code.

I also became acutely aware that with my life endangered, I didn’t much care that the people around me were complete strangers, and I quickly morphed into a soldier most adept at following orders.

When you’re handed a pile of aspirin, you chew them. When they need to remove all your clothes, you say, "Do it.” When they need to shave your groin, you quickly nod, "Yes, please do.” When they’re putting a painful radial arterial IV in your wrist and whisper, "You can say it,” you do—because there’s something genuinely therapeutic in a cardiac patient growling an F-bomb through their clenched teeth.

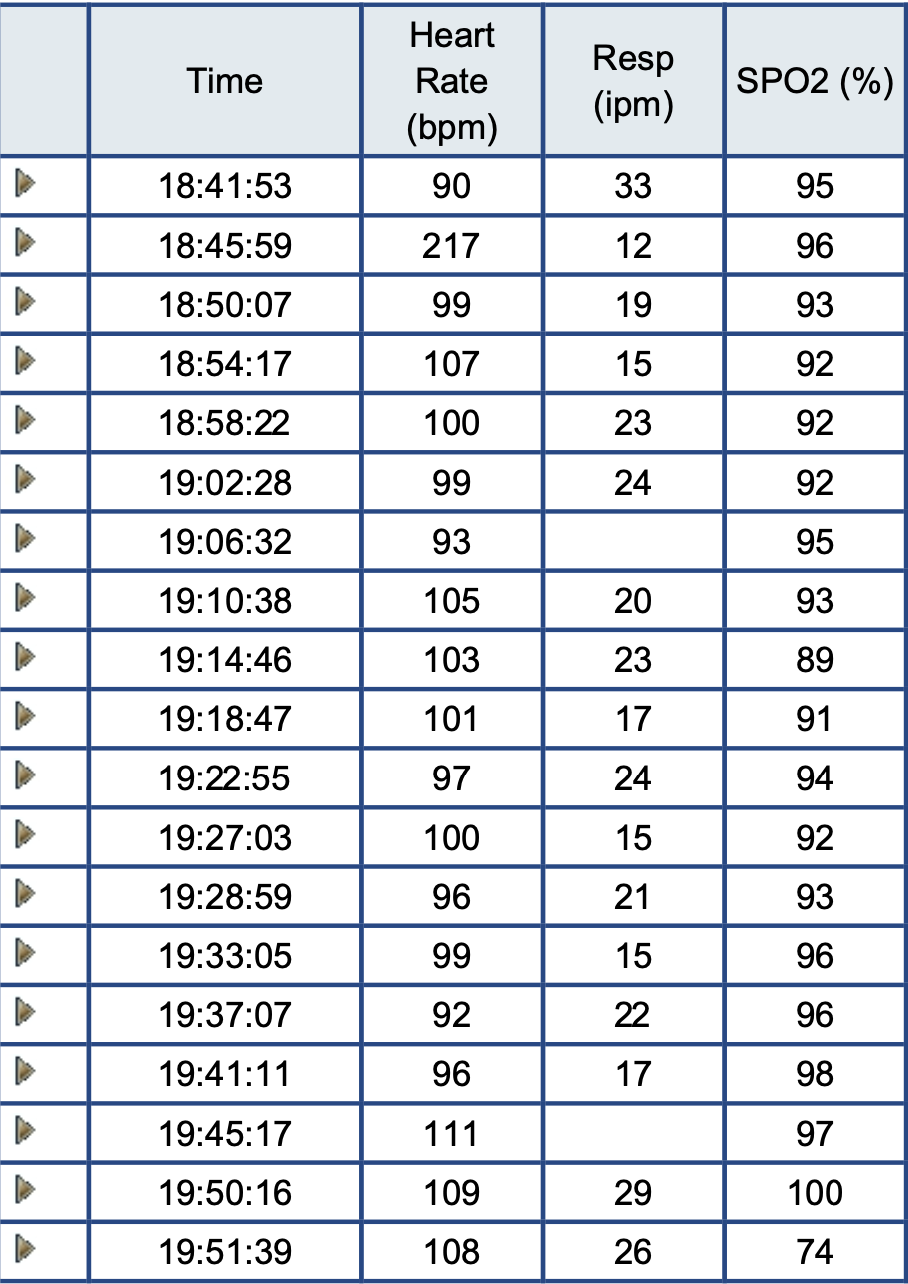

During a brief lull in the action, I learned I’d been prepped for an angioplasty and that members of Providence’s cardiac team were en route to the hospital. A short time later, at 6:37 pm, I was wheeled into the Cath Lab. Minutes later, my heart rate skyrocketed to an incredibly dangerous 217 beats per minute before settling into a more reasonable, yet still high, rate of between 92 and 111 beats per minute.

When the procedure was complete, I learned vascular surgeon Dr. Jon McDonagh had successfully removed a clot caused by a narrowed blood vessel and placed a SYNERGY XD drug-eluting stent that prevented further damage to my heart—ultimately saving my life.

I can scarcely do justice to the exceptional care I received at Providence. From the moment I passed through their doors to my not-so-final farewell later in the week, the professionalism and dedication of every staff member was nothing short of extraordinary. I grew especially fond of my vigilant yet compassionate ICU nurses, who answered every question without hesitation or obfuscation. They were pillars of strength and peace in the days following the madness, and it is to their credit that my initial steps back to health felt less daunting.

On the day of my discharge, I told Alaska Heart & Vascular Institute president, Dr. Linda Ireland, that given I’d waited so long before seeking care, I felt as though things could have played out much worse. She agreed, as did other health care professionals I’ve spoken to this week.

In rationalizing my discomfort as a mere muscle strain, I was in denial about the possibility of a heart attack—perhaps in part because it didn’t at all resemble the dramatic presentations I’d seen in television shows and movies. You know the scenes: an obese and profusely sweaty man clutches at his chest as his skin turns ghostly pale while he slides down a wall before collapsing into a sad, gasping lump on the floor.

I’m not alone in my reasoning. According to the Harvard Heart Letter, nearly half of people who have a heart attack don’t realize it at the time. Dr. Kenneth Rosenfield, Section Head for Vascular Medicine and Intervention at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital, writes that some people mistake their symptoms as indigestion or...wait for it...muscle pain.

"Many people don’t realize that during a heart attack, the classic symptom of chest pain happens only about half of the time,” Rosenfield says. Often, heart attack symptoms manifest as chest discomfort or pressure. Others experience a crushing sensation or deep ache.

From December 27th, when the ‘discomfort’ began, to New Year’s Day, my denial was depriving valuable heart muscle of essential oxygen because it seemed implausible to me that I was experiencing a cardiac emergency as my symptoms weren’t...dramatic or painful enough.

It’s clear to me now that the line between denial and acceptance is perilously thin. Do not wait for discomfort to become unbearable or for your symptoms to fit the dramatic imagery depicted in a Grey’s Anatomy episode. The absence of dramatic pain does not signal safety. It is far better to spend money and time on a false alarm rather than to confront the realities of a neglected heart.

Don’t wait to get help. Some heart attacks are sudden and intense, but others start slowly, with mild pain or discomfort. Learn to recognize the warning signs of a heart attack.